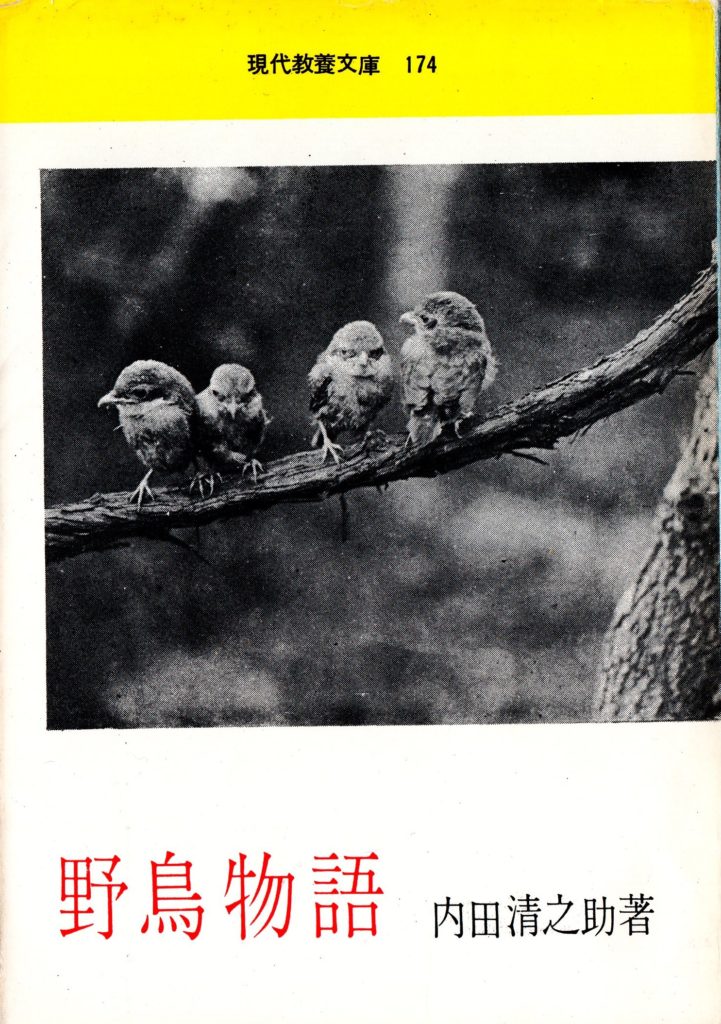

内田清之助 『野鳥物語』

椋鳥と雀の話

先日、インターネットの古書店でなつかしい本に出合った。内田清之助の文庫本『野鳥物語』だ。内田清之助という人は、東京大学教授で大学時代には夏目漱石の英文学の講義も受けたそうだ。中西悟堂とともに日本野鳥の会を創設した人である。

なつかしい、というのはこの本を読んだ思い出ではない。私の父がこの本を好きで「おい、この雛鳥の目を見てみろ、鋭さがすごいだろう」と、よくこの本の表紙の写真を見せてくれたものだ。なつかしく思ったのは、この写真である。モズの雛鳥である。最近はこのように寄り添う雛鳥を「ひな団子」というそうだ。NHK「ダーウィンが来た」でシマエナガのひな団子が紹介されていて、初めてこの言葉を知った。

今回この本を初めて読んだ。とても面白く読めたのだが、何といっても昭和37年発行のものである。鳥類学や野鳥観察などそれ以降、長足の進歩を遂げているはずである。うっかり古い知識を引用しては恥をかく可能性がある。ここではそのような間違いのない、歴史的事実として面白かった椋鳥と雀の米国への移入についての記述をみてみたい。

まず、椋鳥である。

‥‥日本の椋鳥に習性や形態がよく似ているのは欧州の椋鳥である。ことにイギリスでは非常に人に親しまれ、有名な鳥になっている。色は日本のより黒いが、金属的な美しい光沢があり、背や腹に樺色や白色の星が多数あるところからホシムクドリと呼ばれる。ロンドンなど繁華な都会で、鳥などはいないようなところであるが、雀と椋鳥だけは例外でロンドン児の眼をなぐさめめている。アメリカにも東岸一帯にはこのホシムクドリがいる。まえに、椋鳥は新大陸にはいないと述べたが、このアメリカの椋鳥は一八九〇年と一八九一年の二年間にイギリスから移入され、ニューヨークの中央公園に放されたのが以来四十年間に猛烈な勢いで増殖し、東海岸ではほとんど北米を前途にわたって棲息するようになったのである。

内田清之助 『野鳥物語』 現代教養文庫 昭和37年刊

次に雀については次のように記されている。

欧州の雀は欧州全土に分布しているが、アメリカには、もと雀はいなかった。しかし、十九世紀の中葉から二十年間に千五百羽の雀が北米に放たれた。それは当時、アメリカで楡の木が毛虫の害を被ることはなはだしかったので、毛虫退治のために雀を放したのであるが、これが成功して非常な勢いで増殖し、今日では北米の東部一帯にひろがっている。ところがこの雀、楡の木の毛虫は盛んにくってくれたが穀物の方にもえらく嘴を出すので、今では害の方がひどくて困っているような始末である。自然の摂理はじつに微妙であって、そういう風に動物をよその国から輸入したりすることは、なかなか人間の思うようにはならぬむずかしいものなのである。

米国でもあれほどポピュラーな椋鳥と雀が、実はヨーロッパからの人為的に移されたものだと知って驚いた次第である。両鳥ともに現在では増えすぎて害鳥扱いに近いそうだ。

椋鳥はどのように米国に移入されたか

椋鳥はどのように米国に移入されたか

椋鳥の北米移入については、先日Lynda Lynn HauptのMOZART’S STARLINGを読んでいて、もう少々詳しく知ることができた。モーツァルトのピアノ協奏曲との関係について別稿でこの本を取り上げる予定であるが、ここでは、椋鳥の移入についての記述を引用したい。Haupt女史は鳥類学者であり、さすがにその経緯についての説明は詳しい。

Regarding the presence of starlings in North America, some blame Shakespeare. In the 1800s, “acclimatization society” began to form across the country, following successful models in France. It was a vulnerable time for many newcomers to America, who were homesick and hungry for the arts, literature, flowers and birds of their homeland. The aim of the society would be “interesting and useful” to the seemingly deprived New World species that would offer aesthetic and sentimental inspiration through beauty and song.

Lynda Lynn Haupt MOZART’S STARLING Little, Brown Spark

acclimatizationというのはその土地に棲息しない動植物を、他の土地から移入することであるが、1,800年代の米国では、そのための協会が米国各地に設立され始めていた。建国から日の浅い米国人には、自らの故郷でもある欧州、特に英国の風土に近づけたいという気運があったらしい。

Eugene Schieffelin was a pharmacist who lived in the Bronx. He was an eccentric, an Anglophile, and a Shakespeare aficionado. Some say he was also an ecological criminal and a lunatic, but I would argue for a gentler description; perhaps “flawed.” As deputy of the American Acclimatization Society of New York, Schieffelin, it is believed, latched onto the personal goal of bringing every bird mentioned in the work of Shakespeare to Central Park. Armed with his treasured copy of the exquisite Ornithology of Shakespeare, an 1871 volume in which James Harting assembled every allusion to birdlife in the world of the Shakespeare canon, Schieffelin zeroed in on the Bard’s single reference to a starling, in Henry IV. It is a decisive scene: King Henry commands that the willful soldier Hotspur free his prisoner, but Hotspur replies that he will do nothing of the kind until the king agrees to pay the ransom that will free Hotspur’s brother-in-law Mortimer from the enemy. The king flies into a fury and forbids him to mention Mortimer’s name. After the king’s exit, Hotspur imagines a fanciful retribution, and here enters our star:

He said he would not ransom Mortimer;

Fobad my tongue to speak Mortimer;

But I will find him when he lies asleep.

And in his ear I’ll holloa, “Mortimer!”

Nay.

I’ll have a starling shall be taught to speak

Nothing but “Mortimer,” and give in him

To keep his anger still in motion.

その中で現れたのが半ば「狂人」のシェッフェリンなる男、シェークスピア狂でもあった。American Acclimatization Society of New Yorkの代理委員でもあった彼は、シェークスピアの作品に出てくる鳥を集めたハーティングの著書Ornithology of Shakespeareに依り、新世界にいないすべての鳥を英国から移入することを目標に設定する。彼はその中でも、たった一度だけヘンリー四世でのホットスパーの一言にでてくるだけの「椋鳥」に照準を合わせる。

Shakespeare was attentive to birdlife; larks. nightingales, and chaffinches wing and sing their way through the plays and sonnets, and in his unique Ornithology, Harting cataloged every one and quoted the lines in which they appear. The acclimatization societies did in fact try to bring in many of these species, but with the obsessive powers of a true eccentric, Schiellelin fixated on this one slender reference to the staling. Introductions of Shakespearean chaffinches, nightingales, and skylarks, and earlier efforts by Schiefflin to establish starlings, had resulted in nothing but cold, starved dead birds. Eugene resolved that his next starling attempt would not fail.

協会は、実際にそれらの多くの鳥を移入する計画を実行に移すのだが、最初の試みは完全な失敗に終わる。しかし、狂気に取付かれているシェッフェリンはあきらめず、自らの資産を投じて2度目の挑戦を行うのだ。これが内田清之助の「1890年と1891年に」という記述に対応しているのだろうか。1年のずれはHaupt女子の記述が正しいのだろう。

In 1890, he paid out a princely sum from his private stores (surely enough to satisfy ransom) to purchase eighty starlings from English source, and he perhaps laid out a bit extra to ensure that they would be well tended on their long journey to the New York port, where Schieffelin met them in person, enlisting help from his houseman to carry their crates. He released his bewildered birds on a snowy March day in the middle of Central Park. I think of him there―gloved, worried, flush with hope and an honest, if misguided, love. The release could not have been all he’d envisioned. The birds would have been tentative in the cold and the snow, perching uncertainly in the leafless maples. This was not the romantic bursting into flight that Schieffelin had surely imagined. But eventually the bird lifted into the gray winter skies. Genetic research in sample population across the continent leads ornithologists to believe that all of the two hundred million―some starlings in North America, including my little Carmen, are descendants of Schieffelin’s birds. (It’s interesting to note that our starlings have quantifiably less genetic variation than starlings in their native European range, This is in line with what evolutionary biologists call the “founder effect,” in which the number of animal introduced―in this case, Schieffelin’s eighty-odd birds―is not enough to contain the genetic variation of the original population.)

そしてシェッフェリンがセントラル・パークに放った80羽の椋鳥は全米に増殖し、害鳥として最も「忌み嫌われる鳥」のひとつになってしまったのである。DNA解析では現在の米国の椋鳥は、すべてこの80羽の子孫なのだそうだ。80羽からでは新しい亜種が生れるには、その数が少な過ぎるとのことである。

日本でもブラックバスなどの人為的なものであれ、意図しないアライグマの増殖やセイタカアワダチソウなどであれ、acclimatizationというものは、その多くは予期しない逆効果をももたらすものなのだろう。

私の家の近くの公園でも、時折セキセイインコの大群が訪れるようになっている。

(英語の読み間違いなどがは、SUさんが指摘してくれると思います。その場合は改訂します。)